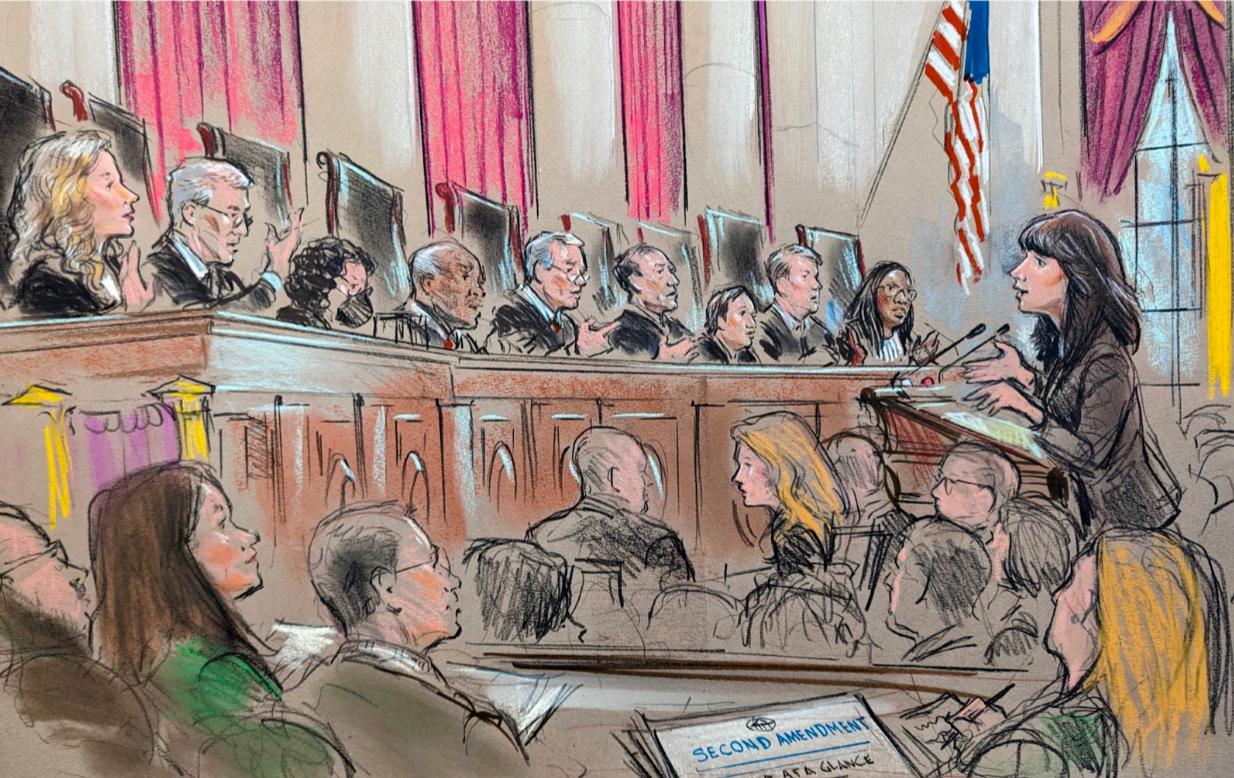

Photo Credit: William J. Hennessy Jr./Courtroom Sketch

Guns In America

According to a Pew Research Center survey from September 13, 2023, six in ten U.S. adults say gun violence is a very big problem in the country today. Amid a backdrop of mass shootings like the one in Lewiston, Maine that left eighteen dead on October 25th, increasing gun violence has made the legal landscape ripe with gun-related judicial challenges. Earlier this year, the Court dealt with Garland v. Blackhawk Manufacturing, a case concerning federal regulations on guns without serial numbers. On November 7th, the Court heard oral arguments in U.S. v Rahmi which involved a Second Amendment challenge to a federal ban on the possession of guns by individuals who are subject to domestic violence restraining orders. Both cases have the potential to be landmark rulings that affect the landscape of American gun ownership and sales.

Garland v. Blackhawk Manufacturing

In 2002, as a result of the Homeland Security Act, the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms, and Explosives (ATF) was established as an independent federal agency within the control of the Department of Justice. Subsequently the ATF gained regulatory enforcement powers within the realm of firearms, explosives, arson, tobacco, and alcohol. They function as an arm of the executive branch and their agency head is appointed by the president. In August of 2022, the ATF amended its regulations and issued a new rule in order “to remove and replace the regulatory definitions of ‘firearm frame or receiver’ and ‘frame or receiver’.” The change in definition was part of an ATF initiative to increase supervision on ghost guns, which are guns that “lack serial numbers or other identifying markings.” The lack of identifying markings make the guns easy to traffick and reduces their traceability, which hinders law enforcement’s ability to solve crimes.

The new language in the ATF rule meant that those who sold untraceable parts that are often used in the creation of ghost guns would have to comply with existing federal law under 18 U.S.C. § 923. 18 U.S.C § 922 details the processes of obtaining a federal firearms license to legally sell, import, or manufacture firearms, munitions, or explosives. It also describes the requirements federal firearms licensees (FFLs) must abide by in order to retain their FFL, such as documentation and fees. According to an ATF summary of the rule changes, they expanded the definition of “‘frame or receiver’ to include a partially complete, disassembled, or nonfunctional frame or receiver that has reached a stage in manufacturing where it may quickly and easily (“readily”) be made to function.” They also said that gun manufacturers must mark the frame of their own or privately made weapons “with either the serial number and their name and city and state or their name and the serial number beginning with the abbreviated federal firearms license number.” Additionally, they strengthened the record keeping requirements for FFL’s by mandating they “retain their Firearms Transaction Records, Forms 4473, and acquisition and disposition records until they discontinue their business or licensed activity.” In response to this, several gun manufacturers sued Attorney General Merrick Garland in his official capacity as the leader of the Department of Justice because they are the parent agency of the ATF.

Nearly a year later on July 30, 2023, the new ATF regulation was invalidated. Judge Reed O’Connor, in the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Texas, issued a ruling that vacated the ATF regulation across the entire country. O’Connor wrote in his decision that “the agency [ATF] acted beyond the scope of its legitimate statutory authority in promulgating [the rule].” The ATF immediately appealed this ruling and their appeal appeared on the Supreme Court’s emergency docket in 2023. The emergency docket allows the Court to hear cases on an expedited timeline with very limited briefing and no oral arguments. The ATF argued for a stay of Judge O’Connor’s ruling, which would allow the ATF to continue to enforce its regulation during the appeals process. The Supreme Court granted the stay and temporarily suspended Judge O’Connor’s ruling while the appeals process continued. This decision was released on August 8, 2023 in a 5-4 vote, with Justices Sotomayor, Kagan, Jackson, Roberts, and Barrett in the majority and Justices Thomas, Alito, Gorsuch, and Kavanaugh dissenting.

Immediately following the stay issued in August, the two gun manufacturers who sued the ATF– Defense Distributed and Blackhawk Manufacturing– sought an individual injunction against the Supreme Court’s ruling. Effectively, this injunction would prevent the Supreme Court’s stay from applying to Defense Distributed and Blackhawk Manufacturing only, thereby exempting them from the ATF rule while the case awaits judgment in appeals court; all other gun manufacturers would still have to abide by the Supreme Court’s stay, unless they also sought their own individual injunction. On September 14, 2023, Judge O’Connor granted the injunction to the gun manufacturers and enjoined the ATF from enforcing its rule on Defense Distributed and Blackhawk Manufacturing.

The ATF filed a second appeal to the Supreme Court’s emergency docket to vacate the injunction issued by Judge O’Connor. Their case was heard, and on October 16, 2023, the Supreme Court released a unanimous order to vacate Judge O’Connor’s September injunction. The Court’s vacatur this time was notably different from the first Supreme Court order because of its unanimous nature, which may indicate that the Supreme Court agreed with part of the ATF’s brief claiming that Judge O’Connor was ignoring the Court’s “authoritative determination about the status quo that should prevail during appellate proceedings.”

After the Supreme Court’s intervention, and while this case progresses through the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals, all gun manufacturers must comply with the ATF’s current ghost-gun rule. In practice, this means that the language of federal laws that govern gun sales, such as the National Firearms Act and the Gun Control Act of 1968, that say “each manufacturer and importer and anyone making a firearm shall identify each firearm,” which extends to the parts used to make ghost guns for the time being. Consequently, gun manufacturers who sell the parts used to make ghost guns are legally obligated to serialize their parts with proper markings, maintain a larger set of records, and improve their sold guns’ traceability. Regardless of the Fifth Circuit’s future determination, this case is likely to end up at the Supreme Court in a future term because whichever side loses in appeals court is likely to appeal again, and the Supreme Court has shown they have an interest in hearing this case by choosing to rule on it twice through their emergency docket.

United States v. Rahimi

The second major gun case of the year, U.S. v. Rahmi, had oral arguments in front of the Supreme Court on November 7, 2023. Rahimi’s case presents a Second Amendment challenge to a federal statute known as 18 U.S.C. § 922(g)(8), which prohibits the possession of firearms by people subject to domestic violence protective orders. These are orders that are issued when someone is “harassing, stalking, or threatening an intimate partner of such person or child of such intimate partner or person, or engaging in other conduct that would place an intimate partner in reasonable fear of bodily injury to the partner or child.”

Between December, 2019 and January, 2021, Zachary Rahimi was allegedly involved in several violent acts both against his partner and other women, including pushing his partner into a car after an argument in a public parking lot and then shooting at a witness to the event. After this incident, Rahimi’s partner sought and received a two-year protective order against Rahimi after the court found that “Zackey Rahimi ha[d] committed family violence” and that “family violence [was] likely to occur again in the future.” The order “prohibited Rahimi from committing family violence and from threatening, harassing, or approaching” his partner and her family, as well as “prohibit[ing] him from possessing a firearm.”

Rahimi went on to violate his protective order on multiple occasions. These violations included showing up at his partner’s house in the middle of the night which led to his arrest, threatening to shoot one woman, and five actual shootings in which Rahimi discharged a firearm at or in the direction of various people. Pursuant to these five separate shootings, police obtained a search warrant for Rahimi’s residence. The search uncovered a “.45-caliber pistol, a .308-caliber rifle, magazines, ammunition, and a copy of the protective order.”

After the search of his home, a federal grand jury in Fort Worth, Texas indicted Rahimi for violating 18 U.S.C. § 922(g)(8). Rahimi attempted to dismiss the indictment based on a Second Amendment challenge to the law; his motion was denied and subsequently he pleaded guilty. On appeal to the Fifth Circuit, Rahimi lost again, as the appellate judges cited a previous decision of their own from 2020– United States v. McGinnis– in which they held that “§ 922(g)(8) passes constitutional muster.”

A Change in Second Amendment Case Law

While the Fifth Circuit was hearing Rahimi’s appeal, the Supreme Court was hearing a case involving the New York State Rifle and Pistol Association (NYSRPA), which is named in this case as NYSRPA II in order to distinguish it from an earlier 2020 case involving the NYSRPA. Prior to this case, courts analyzed Second Amendment challenges by “combin[ing] history with means-end scrutiny.” In other words, the Court would look at whether the regulated conduct in question was within the history and scope of the Second Amendment. If this inquiry was “inconclusive or suggest[ed] that the regulated activity is not categorically unprotected,” the court would proceed to evaluate the law in question under intermediate scrutiny. Under intermediate scrutiny, the government must show that the law “further[s] an important government interest” and that it does so in a way that is “substantially related to that interest.” This legal test changed after the court ruled in NYSRPA II that this two-step test was “one step too many.” Instead, the Court eliminated the intermediate scrutiny test and said that “the government must demonstrate that the regulation is consistent with [the] Nation’s historical tradition of firearm regulation.” Only then “may a court conclude that the individual’s conduct falls outside [of] the Second Amendment.”

Fifth Circuit Reexamines

Following the Supreme Court’s ruling in NYSRPA II, the Fifth Circuit withdrew its previous opinion rejecting Rahimi’s challenge and reconsidered his appeal, in light of the change in Second Amendment case law. The Fifth Circuit said that the intervening Supreme Court ruling “clearly ‘fundamentally change[d]’ our analysis of laws that implicate the Second Amendment” and they chose to rehear Rahimi’s appeal. The Fifth Circuit issued a new ruling declaring 18 U.S.C. § 922(g)(8) facially unconstitutional in violation of the Second Amendment. In their opinion, the Fifth Circuit explained, “the Government fails to demonstrate that § 922(g)(8)’s restriction of the Second Amendment right fits within our Nation’s historical tradition of firearm regulation.” The Fifth Circuit dismissed every historical comparison the government attempted to offer as justification for its actions, saying they were not “relevantly similar.” In light of this new ruling against them, the United States appealed and the Supreme Court granted review.

Briefs in United States v. Rahimi

Solicitor General Elizabeth Prelogar presents two main arguments in her brief on behalf of the United States. First, she claims “the Second Amendment allows Congress to disarm persons who are not law-abiding, responsible citizens.” She supports this claim by citing previous Supreme Court opinions, like District of Columbia v. Heller and NYSRPA II v. Bruen, which said that the Second Amendment protected “the right of an ordinary, law-abiding citizen to possess a handgun in the home.” Solicitor General Prelogar says that Rahimi is not a “law-abiding citizen.” She then describes the historical practices the government has for disarming “irresponsible subjects” in an attempt to show a “long standing tradition” that “history confirms that Congress may disarm persons who are not law-abiding, responsible citizens.” Second, she argues that “Section 922(g)(8) complies with the Second Amendment.” To support this claim, she points to “Section 922(g)(8)’s strict requirements” and the fact that “restrictions like Section 922(g)(8) are commonplace throughout the United States” in an attempt to show that the law is not overly broad or unusual. She also supplemented this argument by saying that people subject to domestic violence protective orders are inherently “not responsible.”

Rahimi’s lawyer, public defender J. Matthew Wright, makes three main arguments in his brief. First, he analyzes the text of the Second Amendment. From this analysis, he points to the court’s decision in District of Columbia v. Heller, where they said the term “the people,” as used in the Second Amendment, “unambiguously refers to all members of the political community” of which Rahimi is still a part. He also says that § 922(g)(8) directly criminalizes conduct explicitly protected through the Second Amendment’s use of the phrases “shall not infringe” and “keep and bear arms.” Third, he argues that “nothing in the history of American firearm regulation remotely resembles § 922(g)(8).” He says that historical alternatives other than disarmament were used to punish abusers, such as “jail” and “surety” which is when one forfeits over money that is returned, contingent upon good behavior. He also asserts that none of the laws Solicitor General Prelogar cites as holistically comparable to § 922(g)(8) “banned and punished a rights-retaining citizen’s possession of firearms in the home.” The last main argument of the brief details how § 922(g)(8) “violates the Second Amendment on its face.” Rahimi and his lawyer have made a facial challenge to § 922(g)(8) as opposed to an as-applied challenge. The difference is that in a facial challenge, the argument is that the law in contention is always– under all circumstances– unconstitutional, whereas an as-applied challenge argues that the law in contention is only unconstitutional when applied a particular way or under a particular set of circumstances. He argues that it is facially invalid because it is a “blunt instrument,” meaning it is too broad and affects only those who “fit the stereotype of a domestic abuser” but misses actual abusers because they are often “never subjected to a [civil protective order].”

A Shifting World and Legal Landscape

These two cases could be emblematic of what may be a rapid rise in firearm litigation. From something as old as the Second Amendment to the new age of ghost guns, no aspect of firearm case law is out of reach. As the country grapples with its relationship to guns, people on both sides will turn to the courts to resolve disputes.