Photo Credit: Christopher Lomahquahu/News21

The Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution states:

For over 156 years, this amendment has guaranteed the automatic acquisition of citizenship to individuals born within the United States and most of its territories and possessions. Discussions about potentially revising this interpretation have occurred, such as under the Trump administration, but it remains the prevailing legal precedent.

Currently, the Fourteenth Amendment grants citizenship to most individuals born on U.S. soil, including U.S. territories such as Puerto Rico, Guam, the Northern Marianas, and the U.S. Virgin Islands. While those born in U.S. territories may lack certain privileges, such as voting in federal elections, they are still U.S. citizens. However, American Samoa, located 2,600 miles southwest of Hawaii, is an exception. Its nearly 45,000 residents do not enjoy birthright citizenship.

Non-Citizen National Status

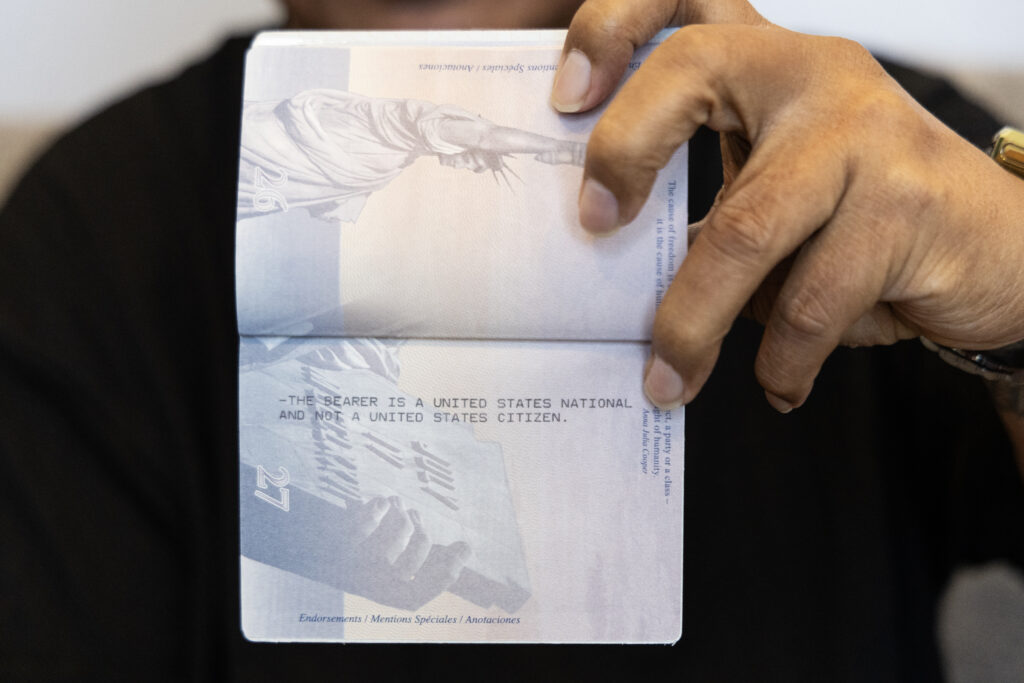

American Samoa is the only U.S. territory where individuals do not acquire automatic citizenship at birth. Instead, they are designated as non-citizen “nationals.”

The difference between “citizen” and “national” may seem minor but carries significant implications. Non-citizen nationals can hold U.S. passports and travel freely within the United States without a visa. However, they are deprived of several rights afforded to citizens, including:

- The ability to vote in U.S. elections, even when residing in one of the fifty states.

- Eligibility to run for public office, as one individual discovered in 2018 when she was ruled ineligible to run for office in Hawaii.

- The ability to serve as military officers or work in federal agencies and law enforcement.

- The legal right to bear arms.

While American Samoans can acquire citizenship, the process involves navigating the complex naturalization system, which includes submitting applications, hiring legal counsel, and passing an exam. Even then, citizenship is not guaranteed.

Historical Context

American Samoa became a U.S. territory in 1900, when local chiefs agreed to cede the territory during the era of Manifest Destiny. In return, the United States pledged to respect Samoan traditions and culture.

Today, American Samoa blends U.S. governmental structures with Samoan customs. The territory elects its legislature and governor every four years through popular vote, mirroring practices in U.S. states. However, village leadership and communal land ownership remain rooted in Samoan tradition.

Some leaders in American Samoa believe that granting birthright citizenship could undermine their “Samoan way of life.” This perspective is central to debates over citizenship but does not reflect the origin of this policy. The denial of citizenship stems from the 1901 Supreme Court rulings known as the “Insular Cases.” These decisions classified U.S. territories as “foreign in a domestic sense” and questioned the feasibility of governing their populations using “Anglo-Saxon principles.”

Legal Challenges

In 2018, John Fitisemanu, a Utah-based healthcare worker born in American Samoa, sued the U.S. government over his inability to vote or qualify for federal jobs. A district court ruled in his favor, declaring that denying citizenship to American Samoans was unconstitutional under the Fourteenth Amendment.

However, in 2021, the Tenth Circuit Court of Appeals overturned this ruling, citing concerns that birthright citizenship might disrupt Samoan traditions. The Supreme Court declined to hear the case in 2022, leaving the current status unchanged.

Broader Implications

The case of American Samoa highlights broader questions about citizenship, cultural preservation, and constitutional interpretation. Some argue that denying birthright citizenship reflects outdated attitudes rooted in imperialism. Others maintain that preserving Samoan cultural traditions is a valid reason for resisting automatic citizenship.

This situation underscores the complexity of applying universal legal principles to culturally distinct communities. For now, American Samoa remains a unique case among U.S. territories.